[Recommend my two-volume book for more reading]: BIT & COIN: Merging Digitality and Physicality

In the upcoming trial of COPA v. Wright, COPA sets out to prove that Dr. Wright is not Satoshi, while Dr. Wright provides evidence that he is.

How do you prove a negative?

There is a misunderstanding about “negative proof”, especially among the supporters of Dr. Wright. The saying is that it is impossible to have “negative proof”.

First, there is an issue of terminology. In philosophy, science, and logic, “negative proof” typically refers to “Argument from Ignorance” (argumentum ad ignorantiam) and “Argument from Absence” (argumentum ex silentio), and is considered a logic fallacy because it mistakes “absence of evidence” for “evidence of absence” to disprove a claim.

That is, it is fallacious logic to take the absence of evidence for a statement as evidence that the opposite statement is true, or the absence of evidence against a proposition as evidence that the proposition is true. In this sense, “negative proof” is indeed impossible.

However, in COPA v. Wright, COPA’s claim is not necessarily the kind of negative proof based on an argument from ignorance or an argument from absence, which would be too obvious to pursue.

What COPA sets out to do is to negate a claim by Dr. Wright that he is Satoshi. You may call it “proof of an opposite”, which is different from “negative proof” defined above. In general, it is an example of “falsification”, which refers to an act of disproving a theory or hypothesis.

But “proof of an opposite” is a mouthful, and not intuitive or conducive to a dialogue.

For convenience, this article will follow a more intuitive and colloquial reading of the phrase “negative proof” and use it to represent “proof of an opposite” or a specific act of falsification, which is what COPA needs to do in this case. Logicians might object to such usage of the term, but this article is not written for academicians.

In this sense, the kind of “negative proof” COPA needs to bring is not logically fallacious or impossible. At least theoretically, it is possible for COPA to establish negative proof of Dr. Wright’s Satoshi claim. It just needs to follow the rule of falsification in logic.

Any statement or proposition, if it is factual or scientific in nature, must be at least theoretically possible to be proven wrong, negated, or falsified. This is the “principle of falsifiability” in science.

Because Dr. Wright’s claim that he is Satoshi is factual in nature, it must be falsifiable or has the potential to be proven wrong.

Forgery and negative proof

The trouble is that strict negative proof based on logical falsification has not been found for COPA in the case of COPA v. Wright. Otherwise, COPA would certainly have included it in its Particulars of Claim (POC).

The POC of COPA does not include “negative proof” based on strict logical falsification of Dr. Wright’s positive claim. Rather, it focuses on negative evidence such as forgery.

COPA’s allegations can be put into two major categories:

- Dr. Wright failed to prove that he was Satoshi in the past.

- Dr. Wright has committed forgeries.

The problem is that these allegations, even if proven to be true, all fall into the category of “Argument from Ignorance” or “Argument from Absence” which does not strictly falsify the claim. It would require equating “proof of something negative about a claimant” with “negative proof of a statement made by the claimant” to be effective. It further requires equating “falsification of a supporting statement” with “falsification of the end statement” to be effective (see below for the distinction between a supporting statement and the end statement). Both have gaps in logic.

Real negative proof

The logical way to falsify a positive claim is to prove either impossibility or contradiction inherently arising from the claim rather than rely on circumstantial evidence of events that carry negative implications to the claimant. In this context, “contradiction” means hard contradiction, the type that causes a logical paradox that cannot be resolved by a variation of conditions.

Real negative proof based on logical falsification is not only possible but can also be essential in many cases.

Consider the following simple example:

You have a car. The car has only one original key, but you are missing it.

The claim: Bob says he has the original key to your car.

A false negative proof: you search Bob’s hands and pockets and don’t find the key, and proclaim that you have proven Bob’s claim is wrong. (This is classic “Argument from Ignorance” because you have not exhausted all possible places Bob might have kept the key.)

Another false negative proof: Bob once wrote an article describing secure ways of keeping and using a key, but when you followed the instructions he provided in the article, you could not find any key because the information given in the article was either hypothetical or incomplete. (Such evidence has nothing to do with whether Bob has the key or not. His article is not even an attempt to prove that he has the key. It is thus irrelevant to the question. Even if you could characterize the article as an attempt to prove his statement, it is Bob’s failure to prove a positive proof, which is different from a negative proof. See below.)

Yet another false negative proof: You point to evidence that Bob has lied in the past about why he has the key and how he kept it. (This is an example of “Argument from Absence” because Bob’s lying about the key just means he has failed to provide evidence that he has the key, but such absence of evidence does not contradict or exclude the possibility that he does have the key.)

An example of true negative proof: Alice shows up and presents the key in her hand. (This is an example of proof of impossibility because there’s only one original key, which Alice has, making it impossible for Bob to also have the key simultaneously.)

Consider another example:

The claim: Bob says he took the famous photo of “Tank Man” during the Tiananmen Square protests in 1989.

A false-negative proof: you find that Bob could not produce the original film of the photo. (This is false because there is no impossibility or logical contradiction here. The one who took the photo may have a variety of reasons for not wanting to or not being able to present the original film.)

Another false negative proof: you find evidence that the person who took the photo called the event “Tiananmen Square massacre”, but Bob said things in the past that seemed to be sympathetic to the Chinese Communist Party. (This is false because discrepancy in words, or even inconsistency in meaning, in what a person says or believes, does not constitute a logical contradiction – see more below.)

A true negative proof: you discover the evidence that during the entire month of June 1989, Bob was stationed in Berlin and never went to China. (This is an example of negative proof based on impossibility.)

Another true negative proof: Jeff Widener shows up with all evidence that it was he who took that photo. (This is an example of negative proof based on contradiction.)

These examples show that it is possible to have a negative proof, but one should not confuse a false negative proof with a real one.

True negative proof in the context of Satoshi’s identity

The above is not a mere academic discussion. An excellent example of negative proof in a specific context of Satoshi’s identity is illustrated by Jameson Lopp.

Mr. Lopp wrote a piece to present negative proof of the claim that Hal Finney is Satoshi. He used the specific and approvable activity time frames of Satoshi and Finney to prove that it is impossible for Finney to be Satoshi because he could not be running a 10-mile race in Santa Barbara, California, on Saturday, April 18, 2009, at 8 AM Pacific time, while simultaneously sending 32.5 BTC to Mike Hearn via a verifiable transaction as Satoshi did.

What Mr. Lopp presented was legitimate negative proof.

Although nothing involving humans can be 100% certain, this is the strongest type of “reverse alibi” evidence to disapprove of a false claim of the Satoshi identity.

The same is true with Dr. Wright’s Satoshi claim.

A simple and valid negative claim can shut him down.

For example, why doesn’t COPA extend the discovery to find one or more windows (periods) of provable activities of Satoshi and Dr. Wright to show a contradiction or impossibility?

Such windows do exist. Find Dr. Wright’s travel itineraries from 2008 to 2010 and compare them with Satoshi’s known activities. Just finding one occasion in which Dr. Wright was on a flight while Satoshi was active online would have provided strong negative proof. The burden would fall completely on Dr. Wright to refute the negative proof.

There is no fundamental barrier for COPA to make such a discovery. In fact, there is no reason to suspect that Dr. Wright might refuse to comply with such a discovery request.

Or, why can’t COPA focus on Satoshi’s evidently necessary skills, such as the knowledge of computer science, programming language, and cryptography, and illustrate by contrast that Dr. Wright does not possess such skills?

Or, why can’t COPA point out the level of Satoshi’s involvement in the Bitcoin project was so high from late 2008 to 2010 that it would necessarily require a full-time involvement, and therefore, any person who claims to be Satoshi could not have been in another employment at the same time?

Just a single negative proof would create an incredible amount of legitimate pressure on Dr. Wright’s claim.

Yet, COPA produces no such negative proof. Zero.

Instead, COPA focuses on circumstantial evidence for negative events (which, as discussed above, is different from negative proof), such as failure to prove the past or alleged forgery.

Why? It certainly cannot be that COPA and its lawyers are so ignorant that they don’t understand the difference.

It is simply because there is no such negative proof in the case of Dr. Wright. It is not that negative proof is inherently impossible (as many have misunderstood), but because, in the specific case of Dr. Wright, there simply is no legitimate negative proof based on either impossibility or contradiction.

Jameson Lopp, who gave strong negative proof to reject the Hal Finney Satoshi claim, has not produced concrete negative proof of Dr. Wright’s claim. There is no lack of motivation or resources. Mr. Lopp is one of the strongest deniers of Dr. Wright’s Satoshi identity claim.

No one in the world has. See the next section for more on this point.

It’s the reality that speaks.

A smearing campaign is therefore the only thing left for COPA to do. The second-best choice for COPA is to find Dr. Wright’s culpability of a scandalous nature (such as fraud or deception) and then use it to discredit (impeach) him and all his evidence. Such a tactic will largely rely on subjective confusion and psychological impact rather than sound and objective logic, but it still could be effective. It’s proven to be extremely effective in the sphere of social media, and it could also be effective in the courtroom. It may be much harder to confuse a court than people on social media, but it is possible, especially when the court has to face an overwhelming amount of information and confusing complexities of the related issues. See the key in COPA v. Wright.

Burden of proof

But why does COPA bear the burden of proof when it comes to providing negative proof with regard to Dr. Wright’s claim that he is Satoshi?

Whether it is in science or legal proceedings, who bears the burden of proof is critical.

The general aspects of falsification can be summarized as follows:

- Hypothesis 0: The base hypothesis that is presumed to be true unless falsified

- Hypothesis a: An alternative hypothesis that aims to prove the base hypothesis 0 is incorrect

- One who advocates the alternative hypothesis bears the burden of proof.

If data (such as test hypothesis a is considered valid.results ) is found to contradict hypothesis 0, then the alternative

It is important to note that in the above-described falsification process, the alternative hypothesis a does not aim to establish any new truth (which would require a separate process), but only aims to prove that the base hypothesis 0 is incorrect. Further, failure to prove the alternative hypothesis a does not mean that the base hypothesis 0 is proven. Hypothesis 0 is simply presumed to be true as far as the falsification is concerned. Any effort to positively establish the truth of hypothesis 0 will require a different process.

In science, the base hypothesis 0 is usually the one that is currently considered to be true or at least more plausible to be true than the alternative based on the existing data. This is what justifies placing the burden of proof on who advocates the alternative hypothesis.

In a legal proceeding, however, a slightly different principle is followed:

- From the onset, the plaintiff, not the defendant, bears the burden of proof.

- As the case proceeds, once a party establishes prima facie evidence for his position, the burden of proof shifts to the other party.

- There is a matter of the burden of proof for the whole case, but in practice, there is also a matter of determining the burden of proof for specific issues.

Following the above principle, it is clear that, in the case of COPA v. Wright, even before Dr. Wright establishes his own case, COPA bears the burden of proof for its negative claim, because Dr. Wright is the defendant, while COPA is the plaintiff.

That is, COPA must bear the burden of providing the necessary proof to falsify the claim “Dr. Wright is Satoshi” as if the claim is the base hypothesis 0 presumed to be true.

Further, if Dr. Wright produces evidence to positively establish at least a prima facie case that he is Satoshi, the burden of proof is more clearly on COPA.

Therefore, concerning the negative claim, the burden of proof is squarely on COPA. The only way to meet that burden of proof is through logical falsification, which requires proof of either impossibility or inherent contradiction to the end statement “Dr. Wright is Satoshi”, rather than beating around the bush by finding problems and inconsistencies in the peripheral areas.

Negative proof through falsification, its fundamental nature, and practical implications

As said above, negative proof based on logical falsification does exist and can be found, and it isn’t hard to understand.

But how come there is so much confusion surrounding it?

People are not confused by the general definition of negative proof but are confused by actual applications involving a logical structure of multiple layers of statements.

From an abstract point of view, proof is always about a certain statement, namely whether the statement is true or false.

The world we live in requires a variety of basic elements, including time, identities, relations, states, conditions, events, and values, to be adequately described. However, when it comes to proof of truth, everything that needs to be approved can be abstracted as a statement or a structure of statements.

Therefore, all proofs are about the truth or falsity of a certain statement. In that, every statement may have a positive proof or negative proof, or lack thereof. It is simple at this abstract level.

The complexity arises because the statements we encounter in human life are not unrelated items scattered on a flat surface. They are hierarchical.

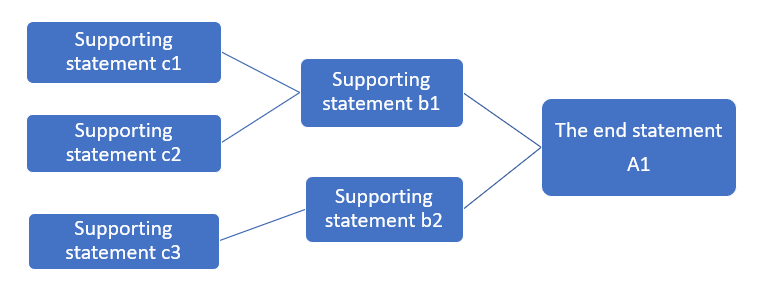

The basic structure of a hierarchical statements can be illustrated as follows:

In the above example, we have multiple layers of supporting statements b1, b2, c1, c2, c3, etc., which collectively support the end statement A1, the ultimate conclusion of this particular logical structure. Of the supporting statements, some are in the middle, which can be a sub-end statement (such as b1 and b2)supported by the lower statements (c1, c2, c3).

Every discussion, debate, or argument has its own logical structure of statements, like the one above. A legal case tried in the courtroom is no exception.

So where does the confusion come from?

Most confusion comes from invalid cross-statement applications and cross-layer applications of a certain proof.

For example, when a negative proof is provided to negate supporting statement b1, one could be misled to conclude that all other supporting statements (e.g., b2) are also negated and further conclude that the end statement A1 is negated. In this case, even if the negative proof regarding supporting statement b1 is valid, the conclusion about the other statements, especially the end statement A1, is erroneous.

Therefore, the problem is not that negative proof is categorically illogical, but that people often make invalid or illogical cross-statement jumps and even cross-layer jumps based on an otherwise valid negative proof of a certain supporting statement. If the negative proof of the supporting statement is even invalid to begin with, that is a different story because such invalid proofs are usually rather transparent. They can be argued and debated, either refuted or established, but they don’t cause logical confusion. It is the invalid application of limited proof across statements or even across layers that causes confusion. Skillful debaters often use such tactics to mislead people.

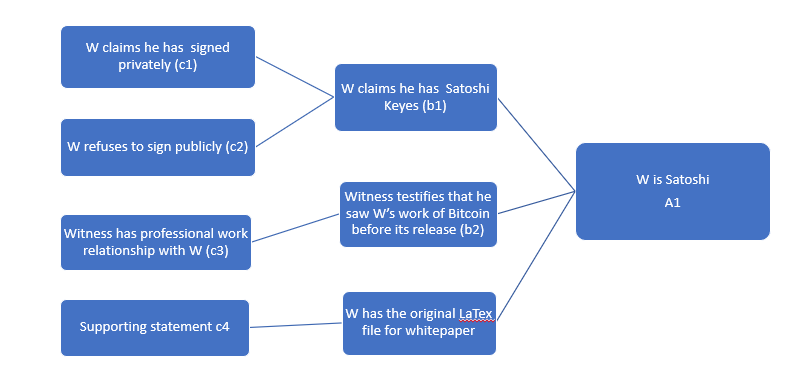

In the case of Satoshi’s identity, we may have the following structure (oversimplified for illustration):

If Dr. Wright wants to prove he is Satoshi, he must meet the burden of proof to positively prove that his statement is true.

COPA may attack any particular statement in the above structure of statements to prove that the statement is untrue. If successful, it would be negative proof of that particular statement. Every successful negative proof weakens Dr. Wright’s evidentiary structure that supports his claim. Such attacks, if substantiated, are both logical and legitimate.

But one should not jump from negative proof of one statement to another, especially not from a supporting statement in a sub-layer to the end statement in the final layer.

It is important to note that, in each layer, negative proof of one statement just takes out that statement. Unless there is an inherent logical connection to other statements in the same layer, the other statements may continue to provide support to the statement in the upper layer. Assuming otherwise is committing a logical error of argument from ignorance or argument from absence.

Evidentiary rules indeed allow impeachment of a witness through the impeachment of a statement by the witness. These rules, however, are strictly and narrowly defined. Impeachment of a witness may discredit other statements the same witness makes and solely supports but does not discredit a statement made by the same witness if the credibility of the statement depends on another independent source. Further, it does not discredit statements made by others, even if the statements are related to the impeached witness.

Even if COPA takes out all relevant supporting statements by point-to-point negative proofs, it only means that Dr. Wright has failed to meet his burden of proof to prove that he is Satoshi, but does not mean that COPA has met its burden to prove that Dr. Wright is not Satoshi.

From the above illustration, it is clear that the only way for COPA to prove Dr. Wright is not Satoshi is to provide direct negative proof to refute the end statement “Wright is Satoshi”. To do that, it must reason for logical impossibility and contradiction rather than resort to sentimental ambiguity.

If Dr. Wright really is not Satoshi, such negative proof must exist.

In fact, such a negative proof can be easily applied against an arbitrary person who claims to be Satoshi. For example, Satoshi is certainly a native or at least highly professional English speaker. Any claimant who doesn’t have a level of commensurate mastery of the English language would face immediate negative proof. Likewise, Satoshi certainly has a high level of knowledge in computer sciences and cryptography. Any claimant who doesn’t have such knowledge faces immediate negative proof.

The only reason why such negative proof is unavailable in Dr. Wright’s case is because he evidently meets all these requirements.

However, there are more specific characteristics known of Satoshi that could pose a meaningful challenge to even a claimant like Dr. Wright.

As Jameson Lopp demonstrated in his article, activity patterns during specific times may present strong negative proof against a claimant whose pattern does not match that of Satoshi.

Yet, as said above, COPA does not even make an effort to find a negative proof to the end statement but rather focuses on negative proofs of the sub-layer supporting statements, hoping that the court would be led to jump across the layers to reach a logically invalid but psychologically effective conclusion.

In fact, outside the courtroom, no one else has found any convincing negative proof against Dr. Wright’s claim. So far, the closest thing is one notorious episode in which someone anonymously signed a message claiming Wright was a fraud using the private key of some addresses found in the list provided by Dr. Wright to the court. But it wasn’t the real negative proof at all. There is no proof that those addresses associated with the key used in the signature are “Satoshi addresses” – addresses known or proven to be that of Satoshi. Even if those addresses at one point in time belonged to Satoshi (there is zero evidence for this hypothesis), there is no evidence that they still belonged to Satoshi at the time of the signature. Those addresses were found to be listed in the large list of address inventory provided by Dr. Wright to comply with a court order but are not even formally attested to be Dr. Wright’s addresses, let alone proven to be Satoshi’s addresses.

Therefore, that detracting signature may be a negative proof to negate the statement “Dr. Wright owns these addresses”, but not negative proof to negate the statement “Dr. Wright is Satoshi”. Note that the former statement is not just different from the latter. It is not even a supporting statement to the latter. They are almost unrelated. Yet people were easily fooled into believing the signature proved Dr. Wright was not Satoshi. This incident itself shows the importance of understanding the structure of logical statements in any argument. It shows how easily an invalid negative proof can mislead the world due to people’s failing to have such a proper understanding.

Negative proof of a negative claim

But let’s turn the table around. COPA’s claim is a negative claim that Dr. Wright is not Satoshi. Can Dr. Wright provide negative proof of COPA’s negative claim?

He can. And he should.

Note that here, the negative proof of a negative claim has the same result as the positive proof of a positive claim but arrives at it from a different angle. The latter is to directly prove that Dr. Wright is Satoshi, while the former is to prove it indirectly by showing that the statement “Dr. Wright is not Satoshi” cannot be true because it causes impossibility or contradiction, or at least unlikely to be true because it leads to improbable conclusions.

The first piece of evidence is the original LaTex file of the Bitcoin whitepaper. If Dr. Wright is not Satoshi, then it would be nearly impossible for him to possess the LaTex file that reproduces a precise copy of the Bitcoin whitepaper. However, it is expected that this issue will be rigorously contested in the trial. COPA is expected to argue the LaTex file is not the source of the whitepaper PDF at all. COPA is also expected to argue that it is possible to reverse engineer such a LaTex file.

Similar evidence for falsifying COPA’s negative claim may emerge from the BOD drive, which likely has pre-whitepaper documents that contain keywords, expressions and descriptions (especially Bitcoin-specific technical expressions) that can only be known by Satoshi before the release of the Bitcoin whitepaper. Such evidence would support a negative proof based on impossibility. It is also expected that the authenticity of the BDO drive will be hotly contested during the trial.

However, there is more.

Silent statements as negative proof

Every piece of evidence is a statement, but there are also silent statements:

What ought to be there but is not.

This is often called “negative evidence”, which is different from “negative proof”.

In the case of Dr. Wright, the statement that “Dr. Wright is not Satoshi,” when combined with the silent statements, logically leads to the following strange conclusions:

If Dr. Wright is not Satoshi, then the real Satoshi has existed in a social vacuum except for his temporary online presence from October 31, 2008 to December 2010. He is completely silent in the face of an imposter making an all-out effort to steal his name and his work.

Even if his own total silence could be explained by assuming that he’s dead, the following facts are still unexplainable: The total silence of everyone in the world who is related to him or represents him and the total absence of everything he has ever done. It means that Satoshi had no family, no friends, no heirs, no agents, no representatives who could vouch for him, yet at the same time, some mysterious force is able to cover up everything he did.

If Dr. Wright is not Satoshi, then Satoshi did not live a real life or have any social life. His entire social circles and connections are silent or dead. His classmates, roommates, and teachers from all the schools he went to, from kindergarten to university, and his companions, friends, and colleagues, all never existed or have completely disappeared. All his school records, university records, formal academic qualifications, employment records, driver’s license, tax records, and any other government records, bank records, credit history, or anything a normal citizen could have enjoyed or relied upon, cannot make any appearance or connection as if they never existed. None of the equipment, especially

But all that screams an extreme form of impossibility because such a human being is either a total myth (does not exist) or is someone whose real identity is wrongfully rejected.

After over a decade of development and accumulation, one but only one proposition has emerged that can resolve the above impossibility. That resolving proposition is simply this:

Satoshi is Dr. Wright.

Once one allows that proposition, all factual and logical difficulties, including the above-illustrated impossibility, disappear. The Satoshi universe suddenly comes into order, connects with reality, and makes sense. It is an on-and-off switch, a yes-and-no separation, and a true-and-false division.

But the world continues to reject the only reasonable proposition. It is because the world does not follow facts and logic but rather impressions, sentiments, emotions, narratives, personal beliefs, preferred values, and entrenched economic interests. Jameson Lopp is an example. Knowledgeable and having obviously investigated

COPA is the corporate Mr. Lopp and more. COPA may also be influenced by value beliefs

Stylometry analysis

So far, we have not mentioned stylometry analysis, which has been a favorite topic of the anti-Wright community.

Neither has COPA in the lawsuit. There is a reason for that.

Stylometry analysis can be relevant when more direct and better evidence is unavailable, but can also be fallacious. It is not real negative proof for falsification (which is not a casual term to be thrown around but has a strict logical definition, as explained in this article). Even if a few mismatches are actually found, they need to be weighed against matches that can be more numerous or most substantial, and more importantly, must be weighed further against evidence in different categories.

Inconsistencies in style or in words don’t often constitute a real logical contradiction because they can be explained away by certain variations in conditions. In addition, such inconsistencies are often a result of the differences in contexts.

For example, Dr. Wright is often quoted as having said “Bitcoin is not about decentralisation” or something along that line. This is quoted against what Satoshi wrote in a post on February 11, 2009: “[…Bitcoin. It’s completely decentralized, with no central server or trusted parties, because everything is based on crypto proof instead of trust.” The allegation is that those two statements are contradictory to each other, and therefore Dr. Wright cannot be Satoshi.

However, such an allegation confuses “discrepancy in words” with “inconsistency in meaning”, and further confuses both with hard “logical contradiction”, which is what supports falsification.

First, “discrepancy in words” in itself is superficial. Words can mean different things in different contexts. Saying things that seem to be discrepant in words does not necessarily lead to inconsistency in meaning.

From a broader point of view, it should be noted that the concept of “decentralization” is not well defined in the context of blockchain and cryptocurrency. It can mean different things in different contexts. (See: Decentralization, a Widely Misunderstood Concept.)

Satoshi’s statement of Bitcoin being “completely decentralized” refers to its not relying on a central server or trusted parties. If one wants to find a true inconsistency in meaning, one should find a case where Dr. Wright said anything inconsistent with this feature of Bitcoin. I am not aware of any such instance.

On the other hand, Dr. Wright has consistently criticized the kind of decentralization based on mathematical even-distribution of the nodes and has emphasized that Bitcoin is not about that kind of decentralization.

Even in the clear meaning of “decentralisation” defined by Satoshi, Dr. Wright has been consistently saying that decentralization itself is never the purpose of Bitcoin, but only a means to achieve a distributed timestamp server that supports a Peer-to-Peer electronic cash system.

There is no reason to believe that Satoshi should disagree with that, or could not have thought or said the same. On the contrary, the whitepaper and Satoshi’s

Second, even “inconsistency in meaning” does not necessarily cause logical contradiction. Inconsistency in meaning is semantic inconsistency and is more substantive than mere discrepancy in words. However, if someone is found to have said something that is inconsistent in meaning with what a certain identity is known to have said, it does not falsify the claim that the person is the same as the identity.

Semantic inconsistency is not the same as the kind of logical contradiction required in falsification. Logical contradiction means a hard logical paradox that cannot be explained away by some variations of conditions. Semantic inconsistency is not that. Anyone could have said things that are self-contradictory, especially if the statements are made at two different times separated by a long period. People’s minds change. People’s perspectives and emphases change. People also forget or momentarily ignore what they said a long time ago. People sometimes don’t care.

Third, if one insists on calling both a discrepancy in word and an inconsistency in meaning a contradiction, then discrepancy in words is superficial contradiction, while inconsistency in meaning (semantic contradiction) is soft contradiction. Neither of them amounts to hard logical contradiction, which is required by logical falsification.

Overall, discrepancies in stylometry, especially those in isolated cases, are not the same kind of contradiction identified by Jameson Lopp. The latter is physical, has been deposited in the history of time, and is not malleable, while the former is intangible, evolves with time, and changes with conditions and environments.

Arguments based on discrepancies in stylometry, especially those that are taken out of context, can be easily dismantled in a lawsuit. There’s a reason why COPA is not even presenting that kind of evidence to the court. COPA has a competent legal team.

Forgery allegations

The anti-Wright community likes to say that Dr. Wright has committed numerous forgeries.

Firstly, as discussed above, forgery is not a logical negative proof. But we should also bear in mind that forgery is a serious accusation and needs to be proven in court by clear and convincing evidence.

COPA will try to prove it in court. There are numerous documents. COPA has picked some of them as a target and will make a huge effort to prove forgery in those documents.

I am curious about the outcome. But I also point out the logic:

— Showing that something could be altered is not the same as finding the thing was actually altered.

— Finding a document was actually altered is not the same as finding the document was intentionally altered.

— Finding a document was intentionally altered by someone is not the same as finding the document was intentionally altered by the defendant.

— Finding that a document was intentionally altered by the defendant is not the same as finding a forgery committed by the defendant. (In a forgery allegation, the alteration must not only be intentional but also for a specific purpose to deceive.)

— Finding actual forgery of certain documents does not automatically cancel the validity of all other documents. (There is indeed an impeachment effect, but as discussed in the article, impeachment is narrowly defined in evidentiary rules.)

— And finally, the establishment of negative proof of a supporting document is not the same as establishing negative proof of the end statement (it only weakens the support to the end statement to the extent that the negated supporting documents are no longer effective).

Even if proven, forgery does not constitute a logical negative proof. There are opportunities for COPA to establish direct negative proof against Dr. Wright. But COPA is avoiding taking them up. Instead, it focuses on forgery allegations.

At least COPA’s allegations will be tested by the trial. In contrast, the forgery allegations made outside of legal proceedings have no legal basis. They are just being flung around freely in social media, causing a moral hazard.

The human witnesses

A large portion of the trial of COPA v. Wright will focus on multiple documents, each equivalent to a statement. From an evidentiary point of view, it is necessary to contest these documents as long as they are deemed relevant. But I hope the judge does not get lost in the forest.

Besides the documents, the firsthand human witnesses are critical.

Up till today, the world has relied on human testimonies. There were a lot of injustices in this human system, but overall, we did fine because human conscience has been and is still operative.

This is especially so when it is a trial court witness under oath. There is a good reason that all common law-based legal systems have strict evidentiary rules about witnesses, differentiating a firsthand witness from hearsay and factual evidence from an opinion.

The importance of this cannot be over-emphasized. It is common for people to confuse the evidentiary value of factual evidence and opinion evidence. “Factual” does not mean you must accept it. It means that the evidence is factual in its nature, in contrast to a mere opinion. For example, in the event of a fire at 10 AM, if a witness says, “I saw a man wearing a red jacket entering the building around 9:50 AM,” that testimony is called factual evidence. Whether you believe the witness is telling the truth or not, or whether this leads to the conclusion that the fire was caused by arson, is a different matter, but the testimony is factual in nature. In comparison, if another person says, “I believe John Smith probably started the fire because I believe he is a bad guy,” that is an opinion. The witness could be right about John Smith, but what he said is not factual evidence.

Opinions can be created, manipulated, spread, and become codependent, and people don’t necessarily violate their conscience when they stand by an opinion.

In contrast, factual evidence is independent. If it is false, it has to be manufactured by the witness himself in a positive violation of the person’s conscience.

Often, factual evidence is irrefutable because it is simply there in the public’s eyes. How one uses the evidence to draw a conclusion depends on how one estimates probabilities, but the evidence itself is factual, and you can’t simply brush it away as if it were somebody’s opinion.

But alarmingly, our society is quickly becoming so corrupt and cynical that it can no longer trust human testimonies, even the testimonies under oath bearing a man’s conscience. The destructive trend will continue to grow until blockchain has started to reshape our world. A provable and immutable global timechain is urgently needed, not to replace human conscience, but to protect and preserve it.

I’m glad that Dr. Wright chooses to prove it in a courtroom using normal human and social evidence because that is the kind of evidence that not only relies on humanity but also gives meaning to humanity in return.

I hope the court gives humanity a chance.

The Bayesian probability estimate based on the totality of evidence

All the above discussions consider each piece of evidence separately as if they were independent from each other.

In real life, however, identities, relationships, and events are related. Evidence does not come in parallel slots but interrelated pieces that stack up upon one another to cumulatively and progressively change the estimate of the probability of a proposition.

This is the teaching of Bayes theorem. When properly estimated using Bayes theorem, multiple pieces of evidence, which each standing alone may not give the proposition a probability too much higher than 50%, can quickly stack up to result in a near certainty of the proposition. See Mathematical Proof that Dr. Craig S. Wright is Satoshi Nakamoto.

Applying the same standard

I try to hold both parties to the same standard. Here is the same standard: If a party wants to present negative proof, it must be the logical type that finds either impossibility or contradiction. It is true for both parties.

If someone alleges that I hold different standards for Dr. Wright and COPA simply because I have reached different conclusions about their positions, that allegation is illogical.

Applying the same standard to different parties can result in different conclusions. This is not even an exception. It is a property of the whole reality we observe and experience. Principled distinction is how truth is discovered and how progress is made. We may demand fairness based on moral principles, but not equal results based on personal interests. When the results are different, find out what has caused the difference. Don’t automatically assume the standard is wrong. Doing that would be committing a logical fallacy. Unfortunately, such logical fallacies have become widespread mind viruses in today’s society.

Summary

COPA can win the case – if it provides convincing negative proof.

But it is not trying to provide negative proof based on straight logical falsification, like what Jameson Lopp did to Hal Finney. Rather, COPA focuses on negative evidence such as forgery. It’s not because they don’t understand the logic, but because they do but are blocked by reality: straight negative proof of Dr. Wright’s Satoshi claim has not been found.

On the other hand, it is not going to be easy for Dr. Wright to meet his burden of positive proof either.

[Recommend my two-volume book for more reading]: BIT & COIN: Merging Digitality and Physicality

Comments are closed